El Tercero: Fernet, Economic Disparity, Venezuela & Marco Rubio

Bienvenidos to the third edition of El Pinchadisco

Welcome to El Pinchadisco. I’m Liam.

I’m glad you’re here. This week, we’re following a similar style to the other two newsletter’s I’ve released, with a little adjustment: all I’ll say is stay tuned for something at the end of the newsletter that will blow your mind. I mean it.

If this is your first time here, welcome — and if it’s your second or third, welcome back. Our journey continues, and I’m grateful you’re here. Whether you like Latin music or not, this is the place for you to be — trust me.

So without further ado, let’s get to it…

What’s hot?

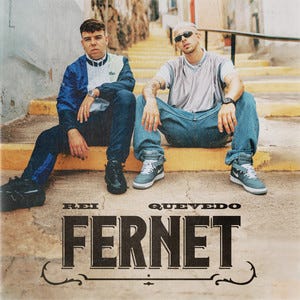

This week we’re doing something a little different. As oppose to writing about the song part of my previous week’s video, I thought I’d take this week to dissect one of my all time favorite songs — Fernet by Rei & Quevedo.

I first heard this song as a junior in high school, when my Chilean cousin came to the United States for the first time. With a plethora of Latin music in a playlist and two Chilean-American boys desperate to get a break of Grand Junction country music, Fernet became a song that dominated my queue, characterized by my brother, cousin, and I dancing and singing to and from soccer practice every day.

It was one of the first songs to reawaken me to the vibrancy of Latin culture that I felt I had lost as a boy growing up in rural United States, transforming the 30 minute drive to school into a nightclub, a concert venue, a soccer stadium. It reminded me of the salty, petroleum infused breeze of Talcahuano, and gave me a bridge to my identity I have so strongly seized now.

First impressions:

Even on the surface, there is no doubt why Fernet is a hit: it’s reggaeton beat bounces smoothly as it follows a lyrical trend synonymous with other Latin music; speaking of love, fame, luxury, and adrenaline.

But, per usual, let’s dive a little deeper:

Produced by the Madrid-born, Canarian singer Quevedo and the Argentinian Rei, the song dives deep into the traditional tenets of Latin culture, challenging societal norms of classism.

Named after the powerful, bitter Italian liquor, Fernet uses objectivity to rebel against socioeconomic status: it critiques it in relation to romance, describing how class should not keep two people apart if they are in love. This can be seen early on in the song, blatantly, as Quevedo describes the visual disgust some might exhibit when viewing two people from two different economic classes.

“Qué mala suerte, conmigo no quieren verte, igual no les gusta mi pinta, no tengo nada pa' ofrecerte”

“What bad luck, they don’t want to see you with me, maybe they don’t like my look, I don’t have anything to offer you” — a reference to the visual appearance in between social classes in Latin culture, as well as the financial difference.

“A tu padre no le gusta mi cadena, pero, nena, tú no olvidas esa noche mezclando mari’ y Fernet”

“Your dad doesn’t like my chain, but, baby, you don’t forget that night mixing mari’ and Fernet” — another use of luxury items to describe wealth and societal status, as seen in other songs I’ve dissected on this newsletter.

“A tu familia no le gusto, pero a ti sí, por eso te robo easy. He viste Prada, bebé, pero yo de DC”

“Your family doesn’t like me, but you do, that’s why I stole you easily. Your look is from Prada, baby, but mine is from DC” — yet another reference to luxury and riches. Prada, a designer brand, is compared to DC, a more regular-priced skate brand.

Zooming in:

The idea brought up in Fernet is one accompanied by many social ramifications. Latin America is the world’s most inequitable region, where the top one percent controls 40% of the region’s wealth, while the poorer half of the region only controls 10 percent. This has affected the vast majority of everyday life — from safety to education — inspiring social unrest, violence, and stagnating economic growth.

There is a long history of corruption, social unrest, and foreign involvement in Latin America. From the US-funded 1973 coup d'état on Salvador Allende in Chile to the current political strife in Venezuela, the tumultuous, cyclical leadership of certain Latin American countries has molded it into a region of economic insecurity.

We’re really going to zoom in:

Take, for example, Flugencio Batista, the brutal ruler of Cuba from 1940-1944 and 1952-1959. Backed by the US financially, militarily, and logistically, Batista was part of the melding of big-stick diplomacy and the growing fear of communism. His rule — structured to garner US support and characterized by a coup d'état — forced the working class into caste-like economic systems, while the top percent flourished and gave Batista continuous support.

Yet this all changed when Fidel Castro overthrew him in 1959, implementing a controversial 49-year communist regime that suppressed other political movements and immorally silenced the voices of those that opposed him. However, he has been championed as a “tireless defender of the poor” and some argue should be “applauded” for his improvements to human rights, such as increased literacy rates and gender equality.

This pendulum swing, using Cuba as an example above, describes the social disparities present in Latin America, from the economy to human rights. Dictator to dictator, one corrupt leader to another — there is not a doubt why the divide between the rich and the poor in Latin America continues to grow, becoming a cemented cycle of economic inequality. While the top percent live like gods, the working class struggles, enduring Atlas-like efforts with the weight of society rested on their shoulders, with little chance of escape.

Let’s talk about NOW.

We could go anywhere from here, when talking about our current world’s economic strife, especially between Latin America and the United States. Rather than focusing on them all — which would be impossible — or focusing on one, where I would feel as though one issue would be more important than another, I would like to briefly touch on two modern day events that I feel are extremely important in this day and age, and very well connected:

First off, Venezuela. After a historic election in July of 2024 between President Nicolas Maduro and Edmundo Gonzalez, Maduro claimed to have won for his third consecutive term — even though reports say he lost by a landslide. For the Venezuelan people, this has led to a dramatic increase in economic divide between the rich and the poor: food shortages, widespread violence, and one of the largest mass migration crises in the world.

In my time in Chile last year, I met a Venezuelan street vendor in downtown Santiago selling jewelry. He told me that he was once a successful business owner in Caracas, yet the government opposed his viewpoints on the social climate of Venezuela and his outspoken critiques of Maduro. Fearing prosecution, jail, and death, he stashed $10,000 on his body — from his shoes to his pockets — jumped on a train, and immigrated to Santiago, leaving his life behind him forever.

Tied to this is — you guessed it — American politics. Media expects Donald Trump to appoint Marco Rubio as Secretary of State as he builds his government for the upcoming four years. The Cuban-American candidate would be the first Latino to serve in this position, and is an example of the effects of the pendulum swing of dictators in Latin America: Rubio’s parents are immigrants from Cuba, escaping Fidel Castro’s regime and finding asylum in the United States.

But Rubio’s views on immigrants don’t line up with his parent’s legacy:

“The tyrant [Maduro] will also happily send dangerous criminals—like the brutal Tren de Aragua gang, which is already wreaking havoc on our streets—the United States’ way. None of this makes life easier for American communities. It shows the White House’s feckless policies have failed across the board.”

While Rubio has expressed that he “recognizes Edmundo González as the President-elect,” he has conveyed to an even greater extent his views on immigration: he doesn’t want it. And as seen above, he champions this belief with rhetoric that has the potential to breed fear and xenophobia, something Trump does so himself.

Thus, with a president who has expressed his desire to use force in Venezuela coupled with a Secretary of State unafraid to describe his clear scathing of Venezuelan immigrants, the alarm bells are ringing:

What does this mean for the Venezuelan working class? Will they be deported, turned down at the border, prosecuted, or worse? Forced to return to a country conflicted at its core, a product of corruption, foreign involvement, and social unrest? Will they have to suffer, while the upper class flourishes, nourishing Maduro’s abuse of the political system?

On a lighter note:

Check this out. This week, I used NotebookLM, Google’s newest AI tool, to transcribe last week’s newsletter into a podcast. The results blew my mind. Check out a video down below of me reacting to the podcast, and I’ll link the full podcast below that.

Here is the full version of the podcast — give it a listen. Absolutely unbelievable.

I’m Liam Cardenas Ferguson, a Chilean-American student studying journalism, film, and environmental studies at Colorado College. Storytelling is a passion of mine, illuminating what only a few know for the knowledge of the public. My art portfolio that contains the stories I’ve told can be found at @liamsxhib on Instagram. If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider subscribing — it’s free.