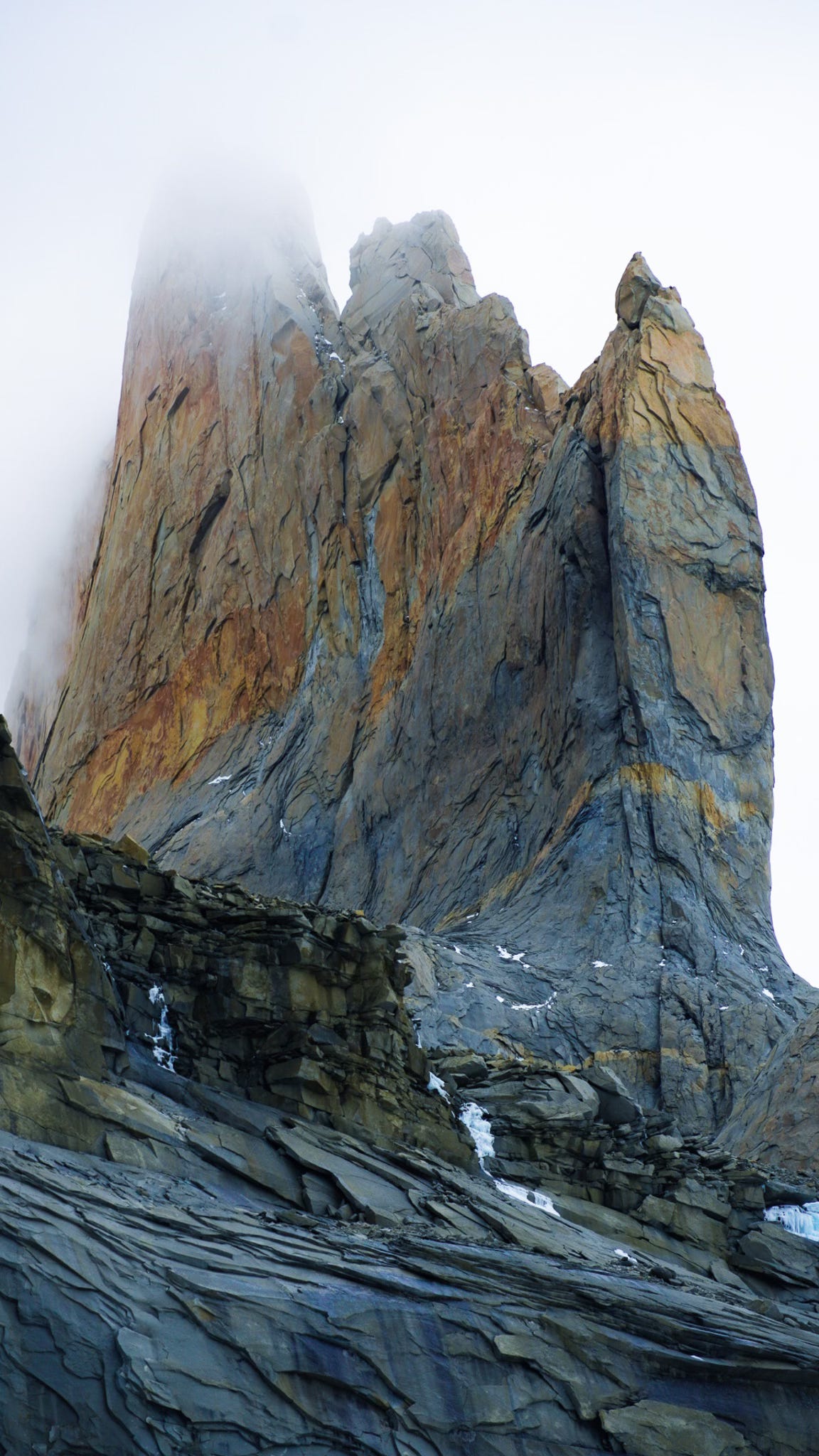

A cold wind swiftly polishes the glaciers of their new snow, whisking Patagonian powder into my face. My eyes tear, my skin burns, my hands nipped, peeling, scabbed. I hang from a table sized boulder nestled into a crack system high in the French Valley of Torres del Paine, on a mountain known as “La Aleta del Tiburon” — The Shark Fin.

The mountain resembles its name to the finest detail: a dorsal fin of granite perched in front of some of the most aesthetic and challenging mountains in the world, scarred with granite fissures the same way a shark’s battle wounds are etched on it’s body. While I hang from this barnacle of stone, a pitch from the summit, I find myself humming the children’s song “The Ants Go Marching” — an interesting choice of music my mind has latched on to, as I haven’t seen an ant in weeks. I don’t know how I remember the words — I haven’t even heard the song in years.

Climbing always brings out interesting parts of my mind. The movement, the freedom, the sensation of being in a place you naturally aren’t meant to be always captures elusive mindsets, memories, and ideas: when I climb, I think of the melancholic songs I used to listen to as a child, people long gone from my life, old passages from books cherished. I find myself planning — something I am not the best at — thinking of grocery shopping, a reminder to check my oil, buy gifts for my family. I don’t know why, but for some reason, my mind goes everywhere but the climb when I’m on the mountain.

Why “The Ants Go Marching?”

As I hang from the rock, 2,000 feet above the ground, the final “Hurrah! Hurrah!”of the song fade away into the French Valley below, expanding into Valle de Agostini and beyond. My climbing partner, Oscar Bortz, cleans the route, stopping once in a while to admire the sheer 3,000 foot face on the other side of the arete we climb.

He appears as a tiny speck below, scrambling around with two skinny strings directing him up an infinite wall of rock. He is a marionette as I take slack in, following my route and the safety of the crack system that zig-zags high into the clouds.

As I watch him, I am reminded of a worker ant. He looks so small down below, dwarfed by the rime-ice, serac-covered summit of Paine Grande. His marionette-like movements remind me of the mundane, wasted lives worker ants live, working out of instinct to provide for their queen. Repetition, consistency, and focus are the keys to survival and the forerunners of perfection, but to what cost do they inhibit the ability to exist?

As I hang belaying — aching, cold, hungry, and contemplative — I can’t help but draw the similarities between our own lives and those of worker ants. Governments, monopolies, people and groups of power controlling the survival of the everyday individual. A burning, raw desire to grow, expand, colonize, perfect — a thirst seen in our own government, foreign policy, and open market. Corporations bustle with corruption, leaders continue to draw us apart from one another, yet we still are only preoccupied with ourselves; our own survival. What does this mean for the future?

Yet we can never improve the future if we cannot learn from the past: and hanging from a rock deep in the Patagonian South, I begin to wonder who else has been here, who else has seen this, and who else has felt this?

With this, I am reminded of a documentary I watched years ago, 6,000 miles away back in Grand Junction, Colorado, when I first became interested in the intricacies of the country of my mother.

El Boton de Nacar (The Pearl Button) is a film directed by Patricio Guzman, one of Chile’s finest documentarians, tying together Chile’s traumatic history of colonialism and dictatorship through an exploration of the natural waterways of the country. And as the rain cleans my jacket and the wind whittles away the dirt from my hands, a part of the film surfaces in my head as if I was back lying on my couch in Grand Junction, warm, dry, and (more) naive.

Once, there was a man named Orundellico.

He was an indigenous man of the Kaweskar people, one of four groups of tribes that resided in Torres del Paine and the surrounding area. In 1830, British Captain Robert Fitzroy sailed into Tierra del Fuego, and by paying the tribe with a mother of pearl button, took Orundellico from his home and back to England, bequeathing him the gentlemanly name of “Jemmy Button.”

A quick learner, Orundellico developed the ability to speak English, adapting to English culture with clothing and appearance. Moreover, he shifted internally, expressing emotions similarly to his captors, something unseen in the tribes of Tierra del Fuego. Kaweskar people are known to appear stoic, expressionless, and internally resilient — a reflection of the savage environment of Southern Patagonia — yet Orundellico rapidly began to express emotions of sympathy, love, and moral decision-making in a Western fashion. Internally, he had been colonized.

After staying in England for three years, Orundellico returned back to Tierra del Fuego with Fitzroy. Upon arriving, it became apparent Orundellico’s experiences in England had changed him forever — he could barely speak his own language, and preferred to speak in English. He wanted to go by Jemmy Button — a name unpronounceable to his own people, who later stole all of his belongings he brought from England, leaving him stranded in a middle-world between his place of birth and his heart.

This sentiment remained consistent throughout the rest of Jemmy’s life. He felt neither Kaweskar nor English — he denied the opportunity to return to Western civilization and remained in Tierra del Fuego, yet taught two wives and multiple children English. He remembered how to use a knife and fork and enjoyed wearing English clothing when presented. He lacked knowledge of the terrain and language of his own home and people, yet was never able to completely embrace the growing presence of Christianity in Tierra del Fuego. He was a man of two identities, participating but never accepting a singular one, making him an oddity to everyone around him.

He died by the hand of an epidemic in 1864, at the age of 49. The pearl button used by Fitzroy to pay for Jemmy fell somewhere into the ocean between Tierra del Fuego and England, lost forever in the volcanic sands and kaleidoscope blue light of the Atlantic.

“Upslack!”

Oscar’s voice reminds me of where I am, and my face reignites, the wind more cold and savage than ever. I study his movements as he gets closer — now only 30 feet away, finishing the final section of an exposed slab before joining me at the lichen covered anchor I hang from.

His movements parallel what climbing is all about: survival. Repetition, consistency, focus — feet nimbly placed on the rock, balanced precariously on the most ludicrous lumps and fluctuations on the granite face. Hands and fingers engaging in the same movement every time — squeezing and crushed into the fissure, every breath, every blink, and every thought a replay of the last.

At its most basic level, survival is a condition of living, but living is not a condition of survival. Even though survival is central to climbing, I do not need to be here — I chose this. I am not surviving here to survive — rather, I am choosing to survive here to live, a privilege only few of us are lucky enough to take part in.

I find that society mimics this. The most wealthy and successful of us continue to turn a blind eye to those who have to survive to survive. On some level, many of us — myself included to our very own government — continue to promote inequity, colonization, greed, hatred, polarization, and more — just so we can individually live.

Living has transcended survival for many of us, and those who have not reached this privileged status continue to suffer at the hands of our ignorance.

“Survival is a condition of living, but living is not a condition of survival.”

Who knows how many more Jemmy Button’s exist out there, from times of ancient to the uncertain future of society? How many people are affected by our desire to live, just as Jemmy was by Fitzroy so many years ago? Which other humans are caught in the middle-world between here and there, living and survival, the past and the future?

How many more buttons are there, from pearl to horn, gently twinkling in the white sands of the Caribbean, resting curiously in the Red Sea, or asphyxiated in barnacles in the Atlantic?

Oscar attaches himself to the anchor, and lays back. We are both living, watching the sun dip below the Pacific Ocean, hanging 2,000 feet above the ground. We have hours of rappelling left — more time to practice repetition, consistency, and focus. We can see the white tips of the Fitzroy massif 100 miles away, the fjords of Tierra del Fuego, and I can almost imagine the Rocky Mountains of my home 6,000 miles away, part of the same backbone of savage peaks stretching from North to South America.

I thank where I am, and almost feel a sense of sadness leaving this rock that has housed my thoughts for the past 20 minutes. I acknowledge that I am living — not surviving — and am grateful. Living here — even with the shared amount of awe between Oscar and myself for this area— has been brutal. I can’t imagine surviving.

We button our shell jackets and tighten our hoods over our helmets. We rappel from the summit, visiting the middle-world between the ground and anchor above. Subconsciously, we both begin humming.

“The ants go marching one by one, hurrah, hurrah.

The ants go marching one by one, hurrah, hurrah .

The ants go marching one by one…”

I’m Liam Cardenas Ferguson, a Chilean-American student studying journalism, film, and environmental studies at Colorado College. Storytelling is a passion of mine, illuminating a bit of what I know for the knowledge of the public. My art portfolio that contains the stories I’ve told can be found at @liamsxhib on Instagram. If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider subscribing — it’s free.

This is incredibly beautiful 😍 the pictures are awesome!!

Amazing read — moving and refreshing from within.